Turnător de la 19 ani. Ca elev, în ultima clasă de liceu. Mincinos cronic. Membru fondator al Grupului pentru Dialog Social. Doctor închipuit şi conducător de doctorate în fals la Universitatea lui George Soros de la Budapesta – CEU. Plantat de M.R. Ungureanu prin Lege (doar proiect, din fericire respins de Parlament) drept preşedinte al Fundaţiei-capcană Gojdu şi pus de V. Tismăneanu în capul la Comisia prezidenţială de “condamnare a comunismului”, până când s-a retras pe “caz de boală”… Beneficiar fraudulos al unor fonduri de la Institutul pentru Studii Avansate – Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, obţinute ca burse post-doctorale, model preluat şi de Patapievici, la fel de fraudulos. Inventator al unor cărţi inexistente, dar pontate ca fiind apărute la Editura Polirom. Conducător al unor institute fictive. Director din partea ICR-ului lui H.R. Patapievici al unei “Şcoli de vară” la Berlin cu turnători ca el şi Andrei Corbea-Hoişie, motiv care a provocat revolta şi protestul internaţional al Hertei Muller, laureata premiului Nobel pentru literatură, alături de alţi oameni de cultură germani originari din România.

Turnător de la 19 ani. Ca elev, în ultima clasă de liceu. Mincinos cronic. Membru fondator al Grupului pentru Dialog Social. Doctor închipuit şi conducător de doctorate în fals la Universitatea lui George Soros de la Budapesta – CEU. Plantat de M.R. Ungureanu prin Lege (doar proiect, din fericire respins de Parlament) drept preşedinte al Fundaţiei-capcană Gojdu şi pus de V. Tismăneanu în capul la Comisia prezidenţială de “condamnare a comunismului”, până când s-a retras pe “caz de boală”… Beneficiar fraudulos al unor fonduri de la Institutul pentru Studii Avansate – Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, obţinute ca burse post-doctorale, model preluat şi de Patapievici, la fel de fraudulos. Inventator al unor cărţi inexistente, dar pontate ca fiind apărute la Editura Polirom. Conducător al unor institute fictive. Director din partea ICR-ului lui H.R. Patapievici al unei “Şcoli de vară” la Berlin cu turnători ca el şi Andrei Corbea-Hoişie, motiv care a provocat revolta şi protestul internaţional al Hertei Muller, laureata premiului Nobel pentru literatură, alături de alţi oameni de cultură germani originari din România.

“ICR-ul crede ca trăieşte pe o altă planetă unde nu există conceptele de demnitate personală şi de integritate morală în ştiinţă?”, a scris Herta Muller în cotidianul de mare tiraj “Frankfurter Rundscahau“, în timp ce “Financial Times – Deutschland” a publicat un articol despre activitatea ICR intitulat semnificativ “Securitate, Sex und Swastika“. Publicaţia internaţională de specialitate evoca protestele scriitorilor germani Richard Wagner si Herta Muller care acuzau “amnezia colectivă” inoculată prin “exportul de turnători” realizat de conducerea ICR prin trimiterea impostorului turnător Sorin Antohi si a informatorului Andrei Corbea Hoisie la o Şcoală de vară de la Berlin. Totodată, renumitul cotidian expert în chestiuni financiare internaţionale amintea existenţa unor fraude constatate de Curtea de Conturi a Romaniei. “Este foarte puţin cunoscut public faptul că exista un Raport al Curţii de Conturi a României care arată că există nereguli în contabilitatea ICR”, publica negru pe alb prestigiosul Financial Times.

Aceasta nu l-a împiedicat pe Antohi să devină, după reproşurile Hertei Muller, “conferenţiar” la Colegiul Noua Europă al lui Andrei Pleşu, fiind considerat într-o publicaţie a acestui ONG drept “un important savant”. Ajunge chiar şi afacerist perdat la Muzeul Literaturii Române sub Radu Călin Cristea şi “lector” în cadrul unei “Academii de Vară” organizată la Iaşi de Institutul Național al Patrimoniului condus de Alexandru Muraru, cercetat pentru furt de documente din Ministerul Justitiei şi “client” al profesorului Corneliu Turianu, secretar al Colegiului CNSAS. Forţat să-şi facă o auto-delaţiune, după 17 ani de “mucles”, numai după ce ziarul Ziua şi Asociaţia Civic Media l-au avertizat pe preşedintele de atunci al României că vor dezvălui public turnătorii şi agenţii din Comisia lui Tismăneanu, în cadrul campaniei “Voci curate în presă şi societatea civilă”. Actul său de auto-turnătorie a fost considerat de un coleg de breaslă drept “un gest de onoare”. După 17 ani de la momentul 1989? Aşa onoare… A, era să uităm: în ultimii ani a fost invitat să-şi pună expertiza la lucru în cadrul unui (alt) “institut”-fantomă, pompos denumitul GeoPol, alături de un Dan Dungaciu şi… Marian Preda! Cine l-a invitat? Patronul: Cozmin Guşă. Vă spun ceva toate înşiruirile acestea de nume, de la Pleşu la Guşă? Vă dau, aşa, o direcţie spre un punct cardinal anume?

Aceastea sunt, oricum, doar câteva dintre calităţile care îl recomandă pe Sorin Antohi şi îndreptăţesc Evenimentul Zilei să-l numească “cărturar”, într-un articol “curios” publicat, discret, într-un week-end prelungit de 1 Mai 2015. Articol din care aflăm, totuşi, şi câteva informaţii. Cum ar fi că procesul înaintat în 2014 (?!) de CNSAS pentru constatarea calităţii lui Sorin Antohi de colaborator al Securităţii a ajuns la Curtea Supremă, în urma unei hotărâri ciudate a Curţii de Apel, care, potrivit EvZ, ar fi decis că “cărturarul” “este colaborator al Securității, dar a respins solicitarea CNSAS de constatare a acestui lucru”. Am citit bine? Da. Aşa scrie la gazetă. Şi mai scrie aşa:

“Pe 15 decembrie 2014, Curtea de Apel București a respins solicitarea CNSAS pentru ca Sorin Antohi – fost membru în Comisia Prezidențială pentru analiza dictaturii comuniste din România- să fie declarat colaborator al Securității. El a avut numele de cod “Valentin”- ca și colaborator și Nicodim- ca urmărit. Asta după ce dosarul său de colaborare a ajuns la CNSAS în anul 2002, dar Colegiul nu a făcut publică sentința de colaborare sau necolaborare cu poliția politică.”

Dacă faptul din urmă, reclamat de Civic Media în 2006, este confirmat în documentele instanţei, atunci avem un caz penal cât se poate de clar pentru cei care l-au acoperit pe co-fondatorul GDS Sorin Antohi, respectiv foştii membri ai Colegiului CNSAS Horia Roman Patapievici şi Andrei Pleşu, la rândul lor membri GDS, care au admis involuntar acest lucru în perioada deconspirării informatorului şi falsului doctor, pe drept cuvânt considerat “probabil cel mai scârbos turnător din lume”.

“The CNSAS itself has been in violation of Law 187/1999 due to the non-disclosure of Antohi’s previous collaboration with the Securitate,” said Dan Visoiu, a Romanian-American lawyer who helped found the Romania Think Tank, a leading research and advocacy group based in Bucharest. – se scrie într-un articol documentat despre Cazul Antohi – The Proffesor of Lies.

În urmă cu ceva timp, Sarah in Romania, o comentatoare atentă a realităţilor României de azi, a revăzut Cazul “Numelui de cod Valentin”, observând cu o oarecare mirare că presa de limbă română a muşamalizat scandalul, în comparaţie cu altele similare sau chiar de mai mică importanţă.Oare de ce?

Reproducem aici atât anchetele şi analizele excepţionale în limba engleză, privind Cazul Sorin Antohi, cât şi curiosul articol din Evenimentul Zilei, în care este căinat “eroul-martir” turnător de la 19 ani:

Curiosul caz al profesorului Sorin Antohi. Judecătorii l-au declarat colaborator al Securității: “I-am turnat, uneori, cu moartea în suflet”

Curtea de Apel București a decis că Sorin Antohi -istoric al ideilor, eseist, traducător și editor român- este colaborator al Securității, dar a respins solicitarea CNSAS de constatare a acestui lucru. Asta după ce în 2006, Sorin Antohi a recunoscut colaborarea cu Securitatea. Decizia finală o va da Curtea Supremă.

Pe 15 decembrie 2014, Curtea de Apel București a respins solicitarea CNSAS pentru ca Sorin Antohi – fost membru în Comisia Prezidențială pentru analiza dictaturii comuniste din România- să fie declarat colaborator al Securității. El a avut numele de cod “Valentin”- ca și colaborator și Nicodim- ca urmărit. Asta după ce dosarul său de colaborare a ajuns la CNSAS în anul 2002, dar Colegiul nu a făcut publică sentința de colaborare sau necolaborare cu poliția politică.

Potrivit motivării sentinței, aflate în posesia Evenimentului Zilei, judecătorul arată în motivare că: “Pentru considerentele expuse, se apreciază că sunt îndeplinite condiţiile prev. de art.2 lit.b din OUG nr. 24/2008, mod. şi compl. şi în consecinţă va fi admisă acţiunea formulată de CNSAS constatându-se calitatea pârâtului de „colaborator” al fostei Securităţi.”

Decizia inedită a fost contestată atât de Sorin Antohi, dar și de CNSAS, la Curtea Supremă de Justiție. Între timp, Sorin Antohi a făcut o cerere de completare a dispozitivului date de Curtea de Apel București.

“I-am turnat uneori, cu moartea în suflet, dar nu i-am trădat niciodată”

Totul începe în septembrie 2006, atunci când Sorin Antohi a încredințat ziarului „Cotidianul” un document cutremurător: o scrisoare prin care recunoaște că a colaborat cu Securitatea.

“Am informat în scris Securitatea despre unii dintre prieteni și pe unele dintre cunoștințe, fără să-i previn, fără să le-o marturisesc post festum până la scrierea acestui text, fără să-mi cer iertare, fără sa-mi asum public acest trecut nedemn și dureros. I-am turnat uneori, cu moartea în suflet, dar nu i-am trădat niciodată: nu am fost agent provocator; nu am primit misiuni de vreun fel; nu mi s-au promis și nu mi s-au creat avantaje; nici una dintre notele mele informative nu a trecut de generalități și de informațiile pe care le consideram deja cunoscute; în toată perioada am ramas ostil Securității și partidului-stat; mi s-a platit cu aceeași moneda”, Sorin Antohi.

Solicitarea CNSAS

Opt ani mai târziu, în iulie 2014, CNSAS cere Curții de Apel București să constate calitatea de colaborator al lui Sorin Antohi.

Datele sunt din sentința Curții de Apel București

- “Aşa cum rezultă din nota raport, din 18.01.1979, consemnată la pct E aferent dosarului nr. 12698 din cuprinsul notei de constatare nr. Dl/1/1463/11.05.2009, „/…/ la data de 29.03.1976, Antohi Sorin a fost recrutat în calitate de colaborator al organului de securitate, primind numele conspirativ „Valentin” şi a fost folosit, pentru realizarea supravegherii informative la cursul post liceal de pe lângă uzina „Tehnoton”, din IAŞI. Recrutarea a avut la bază materialul compromiţător existent despre Antohi Sorin şi a fost realizată de lt. maj. V.F., de la Serviciul 1 al Inspectoratului Judeţean M.l. IAŞI. A.S. a furnizat un număr de 10 note informative, în perioada 16.04.1976-15.05.1978, toate cu conţinut general privind starea de spirit din clasă, mai puţin 2 note informative de cunoaştere a unui coleg, lucrat prin D.U.I.”.

- “În perioada 1978 – 1979, interval de timp în care titularul şi-a efectuat stagiul militar obligatoriu la UM 02114 Ineu, fiind urmărit prin D.U.I. „Nicodim” de organele de contrainformaţii militare pentru cunoaşterea naturii relaţiilor întreţinute de acesta cu lectorul englez L. C.. în această perioadă a continuat să furnizeze informaţii Securităţii (organelor CI).”

Apărarea lui Sorin Antohi

Cărturarul a cerut respingerea solicitării CNSAS și a arătat că a fost șantajat de Securitate și că este o victimă a poliției politice.

Hotărârea Curții de Apel conține și ultimul cuvânt al acestuia:

- În toată perioada 1976-1980 am participat la manifestări culturale considerate ca sfidând politica culturală a PCR. Am fost anchetat şi a fost avertizat de mai multe ori. A fost oprit să publice cărţile pregătite şi a fost dat afară de la conducerea reviste ieşene „Dialog”. A fost propus pentru premiul Herder, dar autorităţile au refuzat să îşi dea aprobarea. A fost un om de cultură urmărit, căruia i s-au încălcat drepturile fundamentale. În perioada contactelor cu ofiţerii de securitate, cărora era obligat să le răspundă, întrucât l-au recrutat sub ameninţarea trimiterii în închisoare, după ce îl avertizaseră că pot fi exmatriculat, nu a scris nimic care să aibă efect asupra drepturilor şi libertăţilor cuiva. Demersul CNSAS pare a-şi propune transformarea sa, cum s-a întâmplat şi în cazul altor oameni de cultură, în ţap ispăşitor. Pentru atingerea acestui scop, creează confuzii şi raţionamente menite mai curând să abată atenţia de la lipsa de relevanţă a aşa-ziselor probe.

- Notele şi Notele de sinteză ale Securităţii sunt o dovadă edificatoare a ostilităţii cu care a fost mereu privit de către Securitate, începând din anul 1976, când a fost forţat să semneze angajamentul cu Securitatea şi până cel puţin la data de 27.12.1988, cel mai recent document în acest sens fiind Raport al Securităţii laşi către Comitetul judeţean al PCR Iaşi pe care l-a şi publicat alăturat Confesiunii mele din anul 2006.

- Reclamantul CNSAS nu aminteşte că din anul 1982 a refuzat, explicit şi categoric, orice formă de colaborare cu securitatea, rămânând doar urmărit, filat (fotografiile de filaj, dintre care am inclus ilustrativ câteva în setul înscrisurilor depuse aferent întâmpinării, i-au fost date de CNSAS), ca obiectiv-problemă dat în sarcina informatorilor de încredere care-şi confirmaseră deja vocaţia şi eficienţa. Am fost considerat un lider periculos al Grupului de la Iaşi (vidi DUI “Cameleonii”, vidi cartea lui Luca Piţu Documentele antume ale “Grupului de la Iaşi”). Am fost interogat, reţinut, arestat, percheziţionat, bătut pe stradă de un grup rămas anonim, dar priceput în aplicarea loviturilor.

- CNSAS nu pare a acorda vreo semnificaţie faptului că Securitatea m-a considerat “nesincer”, m-a suspectat şi m-a urmărit mereu, nu m-a recompensat niciodată. Nu am obţinut aprobarea de a pleca în 1985 la Viena ca bursier Herder, astfel cum primisem recomandare din partea laureatului Adrian Marino. Mi s-au refuzat aprobări pentru orice deplasări în străinătate, cu excepţia uneia singure în RFG, de 20 de zile, în 1988, prilejuită de schimbul dintre Universitatea “Al.I.Cuza” din Iaşi şi Universitatea din Freiburg-im-Breisgau. Cărţile mele nu au putut apărea decât după căderea comunismului. Până atunci, i-a fost retras temporar dreptul de semnătură, chiar şi în periodice.

- Orice demers în justiţie se circumscrie unor norme juridice stricte. Se poate întâmpla să nu existe diferenţe deontologice între o damnatio memoriae civic-politică şi o hotărâre judecătorească, dar în cazul celei de a doua şi al procesului pe care îl presupune, drepturile justiţiabilului se cer respectate mai ferm decât atunci când se încearcă ostracizarea unui individ în spaţiul civic. In niciun caz, nici chiar atunci când o persoană şi-a asumat public o culpă etico- morală, nu pot fi eludate rigorile legii.

- Reţinându-mă de la orice speculaţii, arată că, după 12 ani de la data primei cereri formulată în 2002 de către Grupul pentru Dialog Social şi 5 ani de la Nota de constatare din 2009, la finele căreia reclamantul CNSAS a decis învestirea instanţei cu soluţionarea unei acţiuni pe care avea nu doar posibilitatea, ci şi obligaţia de a o promova, nu la un moment dat, justificat de nu se ştie ce împrejurări, de îndată ce ar fi avut documentaţia necesară, existentă la data de 11.05.2009.

- Votul de 5 pentru, 4 contra cu care, în cadrul şedinţei Colegiului CNSAS din data de 12 iunie 2014, s-a decis sesizarea Curţii de Apel Bucureşti cu prezenta acţiune în constatarea calităţii pârâtului de colaborator al Securităţii, lasă, de asemenea, loc multor comentarii. Crede, însă, că elocventă în cauză se poate dovedi Opinia separată faţă de Nota de constatare, exprimată de df.prof. C. T. (n.r. Corneliu Turianu), consemnată în Adresa nr.536/26.06.2014 a reclamantului CNSAS, motiv pentru care, în conformitate cu dispoziţiile art. 293 alin.2 NCPC, solicită să i se pună în vedere reclamantului înfăţişarea înscrisului conţinând Opinia în cauză, în forma în care se află, de sine-stătătoare sau conţinută în procesul-verbal nr.41 al şedinţei Colegiului CNSAS din data de 12.06.2014.

Cum au motivat judecătorii

Curtea de Apel arată că notele informative din 24 ianuarie 1979 (dosar I 2698, vol. 3, filele 25-26) şi 04 aprilie 1979 (dosar I 2698, vol. 3, filele 30-31), întocmite şi semnate olograf cu numele conspirativ de către Sorin Antohi conţin informaţii care, coroborate cu cele existente în nota raport din 24 ianuarie 1979, “pot contura activitatea de poliţie desfăşurată în calitate de informator de către, respectiv ingerinţa în viaţa privată a celor ce au făcut obiectul delaţiunilor, cu sarcina clara trasată de a observa şi furniza informaţii privind opiniile acestora despre „politica internă şi externă promovate de România socialistă, de Partidul Comunist Român”.”

- De asemenea, potrivit notei informative, datată 04.04.1979, întocmită şi semnată olograf cu numele conspirativ „V.” (dosar I 2698, voi. 3, fila 31) pârâtul a urmărit cetăţeanul român de naţionalitate germană cu prenumele E., fost student la Facultatea de filologie din laşi întrucât „numitul E. a avut relaţii apropiate cu cetăţeanul englez . L., despre care am mai informat. De asemenea, prin intermediul lui L., E. l-a cunoscut pe americanul Paul HIEMSTRA, a cărui prezenţă la SIBIU am semnalat-o mai sus /../’,

- Conform notei-raport, datată 21.04.1981, întocmită dactilo şi completată olograf 2, filele 45-47): ,/…/ A întrebat direct cine dintre colegii sursei lucrează pentru securitate, făcând menţiunea şi F.B.I.-ul contactează masiv străinii. Totodată, a precizat că, după părerea lui, A.S. este informatorul securităţii, el a fost un fraier, a avut încredere în el; a întrebat informatorul dacă va avea necazuri că l-a primit în vizită, s-ar putea să fie întrebat de vizita sa, dacă a fost supravegheat, deoarece este sistem bine pus la punct a fost pus sub observaţie, să nu aibă neplăceri cu discurile care i Ie-a adus, dacă a mai avut relaţii cu B.B. C. /…/.

- Mai mult, prin prisma informaţiilor aflate la dosar, rezultă că activitatea de poliţie desfăşurată de pârât în calitate de informator a fost efectivă, iar atitudinea aleasă cu predilecţie de lectorul englez C. L. reiese că acesta îşi dă seama că are de-a face cu un colaborator al Securităţii şi caută să se protejeze de el. Astfel, activitatea de colaborator a acestuia afectează comportamentul persoanei, întrucât lectorul englez îşi modifică comportamentul, căutând să se ascundă deoarece ştie că este într-un sistem în care este urmărit, iar cel cu care interacţionează este un intermediar sau un agent al Securităţii.

În ceea ce priveşte condiţiile prev. de art.2 lit.b din OUG nr. 24/2008 pentru colaborarea prin furnizare de informaţii trebuie îndeplinite cumulativ două condiţii şi anume informaţiile furnizate Securităţii indiferent sub ce formă să se refere la activităţi sau atitudini regimului totalitar comunist, ori prin cele arătate mai sus pârâtul având numele conspirativ „Valentin” a dat informaţii semnând note informative încă de la data recrutării 1976 până în 1981, iar activitatea desfăşurată în calitate de informator a încălcat dreptul la viaţă privată a celor ce au făcut obiectul delaţiunilor, cu sarcina clasă trasată de a observa şi furniza informaţii privind opiniile acestora despre „politica internă şi externă promovate de România socialistă, de Partidul Comunist Român”.

- Astfel, informaţiile furnizate de pârât au vizat încălcarea dreptului la viaţa privată prevăzut de art. 17 din Pactul Internaţional cu privire la Drepturile Civile şi Politice.

- Nu se poate reţine că furnizarea unor informaţii de asemenea natură nu a fost făcută conştient, având reprezentarea clară a faptului că relatări ca cele prezentate anterior nu rămâneau fără urmări. Altfel spus, prin furnizarea acestor informaţii, pârâtul a conştientizat că asupra persoanelor la care s-a referit în delaţiunea sa se pot lua măsuri de urmărire şi verificare (încălcarea dreptului la viaţă privată), şi, prin urmare, a vizat această consecinţă. (EvZ, 3 Mai 2015)

Pentru documentare: NOBEL PENTRU HERTA MULLER! INTERVIU AUDIO cu Herta Müller despre securistii si turnatorii promovati de ICR si Patapievici

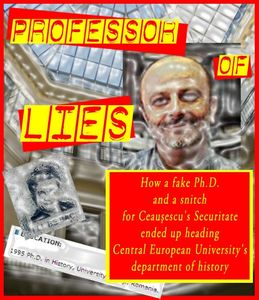

Codename “Valentin” – Sorin Antohi, the ‘Professor of Lies’

(Photo source) Sorin Antohi is a name that chimes controversy. And a lot more besides. He had what should have been an illustrious career ahead of him, but screwed up bigtime. Born in 1957, Antohi is described by Wikipedia as a ‘Romanian historian, essayist and journalist’. He held the position of head of history at the Central European University in Budapest and was an active member of GDS (Grupului pentru Dialog Social). He was also a Securitate snitch and should be shoved in the same bag as the likes of Cornel Todea and Balaceanu-Stolnici….

There’s no scoop in this post. It’s an ‘old’ story, but one I had not heard up until now. The case of Antohi and his sordid past didn’t make much noise in the Romanian press – or at least, not as much as you’d think it would, but Truth v Ambition is a regular game in Romanian politics which these days leaves most people relatively unfazed. It is a tragedy that someone with so much promise ended up conducting both audacious fraud and profound deception that were both so supremely shameful…

So, what happened? In a 2006 open letter published in Revista 22, Antohi admitted to Cotidianul that he had collaborated with the Securitate during the 1970s and ’80s under the codename “Valentin”. That isn’t particularly shocking really, since it happened all the time. What is shocking is that this snitch went on to become a leading authority on the issue of how Romania and countries like it should deal with their turbulent histories. Antohi was also a participant in the official process by which the Romanian government declassified Securitate files and passed judgment on those who secretly served the security services. As part of a campaign called “Clean Voices” – aimed initially at identifying former Securitate agents among the country’s leading journalists – Antohi’s files came under scrutiny. He was forced to confess his secret past, and made to step down from the commission set up by President Traian Băsescu to study such cases that had happened under communism.

He also claimed that he had been persecuted, and physically abused by the same Securitate as a member of the Iasi Group of anti-communist intellectuals, which included Dan Petrescu, Liviu Antonesei, Luca Piţu and others. As an informant, he claimed that he offered non-detrimental information on the political views of many of his close friends. I wonder if these ‘close’ friends saw it in the same light.

Worse still, THIS site says, ‘Antohi actively sought to make sure his own past would never become public knowledge. According to reports in the Romanian media, the government of Adrian Năstase – who, before serving as PM in 2000-2004 was a communist apparatchik, and once published an article entitled “Human Rights: A Retrograde Concept” – intervened to re-classify or destroy the Securitate files of numerous leading public figures, including Antohi. But even if these charges are not proven true, the body then in charge of vetting Securitate files, the CNSAS (National Council for Studying the Securitate’s Archives), apparently broke the law by not disclosing Antohi’s collaboration. (Legislation passed the year before Năstase’s election mandated disclosure for executives and founders of public institutions, such as the Group for Social Dialogue, which counts Antohi among its founder members.) “The CNSAS itself has been in violation of Law 187/1999 due to the non-disclosure of Antohi’s previous collaboration with the Securitate,” said Dan Visoiu, a Romanian-American lawyer who helped found the Romania Think Tank, a leading research and advocacy group based in Bucharest.‘

Apparently, his files disappeared for years. We are talking about someone who participated in a very high-level cover-up

But that’s not all. Wikipedia says: ‘On October 20, 2006, the Romanian press reported that representatives of the Romanian Ministry of Education discovered that Antohi never defended his doctoral thesis in the country. It appears that he failed to write his PhD thesis, and was expelled from the doctoral program of the University of Iaşi in 2000. His CV at the Central European University also listed several books that Antohi claimed were published by Polirom press, but which journalists from the Ziua de Iaşi daily were unable to locate; Antohi was unavailable for comment.’

Pants on fire… For more on that, see HERE. As for why Antohi thought he could get away with it, one answer would be his reputation as a networking genius and self-promoter, and another – his supreme arrogance.

As a consequence of these scandals, he resigned from his position in Budapest and also from the Pasts, Inc. Institute for Historical Studies. He remains an editor of the academic journal East European Politics and Societies to this day, where Vladimir Tismăneanu is chair of the editorial committee.

More scandal saw the light of day in July-August 2008 in Germany and Romania, after Antohi co-directed a Conference with the financial help of the Institute for Cultural Studies. Newspapers in both countries alleged that he had represented himself as the director of two research institutes (one in Germany and one in Romania) which did not exist. At this time the scandal was, in part, revived by Herta Müller who, in a letter to the Frankfurter Rundschau, asked how Antohi, an informer from the age of 19, and someone who had falsified his PhD., could possibly have been invited to an event at a Romanian cultural institute in Berlin. An excellent question indeed.

The Pestiside.hu editor sums Antohi’s fall up perfectly: ‘What drove him to live a life of monstrous lies – first betraying his friends as the informant “Valentin,” and then his students and colleagues as the fraudulent “Dr.” Antohi – was nothing more or less than simple ambition; the willingness to disregard inconvenient boundaries to his own advancement. (This is assuming he didn’t volunteer for Securitate snitch duty out of a sense of duty to a regime he supported.) What makes him more noteworthy than the average liar and betrayer is that he did this while allegedly dedicating his life to the search for truth.’

One of Antohi’s ‘subjects of interest’, shall we say, was Chris Lawson, a British writer/editor, TESOL teacher and published journalist who was living and working in Iasi in the ’70s. This post is principally to share his article (2006) with you, for it makes fascinating reading.

Over to Chris (and thank you for allowing me to copy/paste!):

By Vivid writer: Christopher Lawson

Posted: 30/12/2006

Vivid’s man in Iasi relates how he was implicated in the investigations that revealed Sorin Antohi’s Securitate past

Guildenstern: Our names shouted out in a certain dawn … a message … a summons … There must have been a moment, at the beginning, when we could have said no. But somehow we missed it. Well, we’ll know better next time.

Rosencrantz: We’ve done nothing wrong. We didn’t harm anyone. Did we?

Guildenstern: I can’t remember.

Guildenstern: All your life you live so close to truth it becomes a permanent blur in the corner of your eye. And when something nudges it into line it’s like being ambushed by a grotesque.

(Tom Stoppard: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, 1967)

(Photo source: Sorin Antohi, Securitate collaborator) Since his resignation on 23 October, his name and title at his workplace have disappeared into cyberspace, although he has hardly been absent from the Romanian press over the past several weeks. I am belatedly adding to the column inches for an English-speaking audience, confident that Sorin Antohi’s cunning, calculating face will soon return to our television screens.

The former professor of history at the Soros-funded Central European University, Budapest, and founding director and principal fundraiser of Pasts Inc., the Institute of Historical Studies, resigned all his positions on 23 October when Ziarul de Iasi revealed that he had lied about a non-existent doctorate from the University of Iasi. A month before, he had published a lengthy confession in Cotidianul admitting that he had been an informer for the Securitate in his late teens and early twenties. Like more notorious figures such as Dan Voiculescu, he claimed that nobody had suffered as a result of his activities. Most shockingly, Antohi had also been a member of the CNSAS, the Council for the study of the Securitate archives (www.cnsas.ro), an independent body accountable to Parliament, until he resigned for “health reasons”.

As in all scandals from Profumo to Watergate, the cover-up rather than the case itself constitutes the real offence. The CNSAS, a commission appointed by Parliament six years ago to declassify and pass judgment on servants of the security forces, did not disclose Antohi’s collaborationist past. His records “disappeared”. An ambitious academic who became an authority on the oppressive past of his country, supposedly dedicated to the search for truth, is revealed as an opportunistic liar.

After all, he had had 16 years to come clean about his past as an informer for the communist secret police. In 1990, as a servant of the new Iliescu government, he had even presented himself as a long-time opponent of communism. The Romanian word for copper’s nark is turnator. Somehow the Zulu and Xhosa word impimpi (BrE: collaborator, scab, spy) from the apartheid era, is more expressive.

Impimpi probably lied about his doctorate when the CEU hired him simply because he thought he could get away with it. Antohi, whose learning and intelligence blazes as brightly as his less admirable qualities, had completed nearly all of the formalities required for a doctorate except the defence itself. Universal acclaim greeted his books, although checks are being made on some of the publications he listed.

I write as someone named in his confession. But in the comparatively benign 1970s, as a British lecturer, I was a mere foreigner. My name has been plastered across the Romanian press linked to bird-brained allegations. But that’s the worst that’s happened to me.

Many Romanians suffered unspeakable horrors in the years between 1948 and 1964. As far as I am concerned, it is a badge of honour to be considered “hostile” to a system which had been responsible for the deaths of at least one million people in the whole country, intellectuals, believers of various faiths, village and factory leaders, and old-established families who had created modernity in a previous era.

A further quarter of a million had perished in state institutions, thousands on grandiose construction projects. Countless family members were traumatised. Individuals were kept in a state of permanent terror or forced into exile. Hundreds of thousands of womens’ lives were ruined by Elena Ceausescu’s lunatic ban on contraception and abortion. Even if this semi-literate, vindictive woman may not specifically have forbidden sex education, her actions created several generations of young women deprived of the most basic family planning procedures, many of whom died after botched abortions.

I came to Romania to further my career as a TESOL teacher. I wanted to work at university level, and, newly qualified, knew I would make myself interesting to future employers if I survived a two-year contract in a “difficult” communist country. I chose Romania because I felt that Romanian would be easier to learn than a Slav language.

Although British Council presence in Romania dates from 1938, when Bucharest was one of the first five cities where it set up an overseas office, government-inspired xenophobia reigned in the mid-Seventies. Many Romanians simply could not understand why foreigners came to live in the Socialist Republic. In what passed for humour at that time, British lecturers were told that they had had a reputation for being homosexuals, Jews or spies, or sometimes all three. This so-called joke neatly summed up the homophobia, anti-Semitism and paranoia prevalent in that decade.

Antohi, who was then a teenager still at high school, visited my apartment one Friday evening, and then came regularly. I had a large collection of LPs, which included the complete works of Bob Dylan, kept open house at weekends, and welcomed all and sundry. Most were university students. Antohi had no business coming. I did not know him at all. One of my students introduced him as a rock music fan.

After a number of further visits, when I assumed he was practising his (very good) school English, he started provocative, rather aggressive discussions, and assumed an air of over-familiarity. His behaviour became so strange that I soon smelt a rat. This pipsqueak was too transparent in his dedublarea (BrE: duplicity) to be a good spy.

All the foreign lecturers were spied on, their telephones tapped, their letters opened, their conversations reported, their movements noted.

In this atmosphere I decided that my only recourse was to be myself. Antohi’s controller, a Securitate colonel, lived near the Zona Industriala, the location of my casa de oaspeti (BrE: guest house.) It was very convenient for Antohi to visit both places. My file says I was “unduly sympathetic” to the “co-inhabiting nationalities”, especially the Transylavanian Saxons. Well, I spoke German and found the Saxons far more westernized than the average Romanian intellectual. One young Saxon in particular, an architecture student, visited frequently.

Most entertainingly, I “reported to the Cultural Attache at the British Embassy” and “recruited Romanians” for the service of Her Majesty.

Impimpi is the only possible source for this nonsense. As the heroic veteran dissident Doina Cornea points out, informers typically exaggerate so they appear invaluable to their bosses. In fact, I wrote one annual report each year of my stay about my working conditions at the university, and what it was like to live in Iasi. These reports, entirely concerned with educational matters, did not even name names. I delivered each of the two reports by hand to the British Embassy.

My teaching scrupulously avoided politics. Female students in my classes told me within the first two weeks which students in my classes were informers. My lessons contained only non-political themes, either literary or based on humanistic psychology, an intellectually shaky approach which nevertheless encouraged students to talk about their personal lives, their hopes and dreams. With the American lecturer, I projected documentary films from our embassies on an ancient Russian projector. We ran a borrowing library for students and started an English club for secondary school teachers and pupils.

With a group of dedicated first-year students, I put on three dramatic evenings at the Casa Tineretului, as it was then called. I scoured the work of modern British dramatists to find non-political material, and lighted on Tom Stoppard. A short play A Separate Peace, which concerned a mysteriously healthy man who checked into a hospital formed the centrepiece. The would-be patient just wanted to be looked after by pretty, sympathetic nurses. A brief biography and short extracts from other Stoppard plays made up the rest of the evening.

I was just in time. That summer in London saw a performance of Every Good Boy Deserves a Favour. Andre Previn had challenged Stoppard to put on a play containing a symphony orchestra. The Czech-born playwright chose a Russian prison camp as his setting.

Antohi went on to study English at Cuza University, when he wihdrew from his work for the Securitate. Subsequently he was resident at the Universities of Michigan and Bielefeld and one of the universities in Montpelier. He wrote and published voluminously.

Central and East European, as well as Russian poets have always had a special relationship with Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the almost-definitive version of which was first performed in 1601 in the dying years of the Elizabethan police state. Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s spymaster, had set up and run a tentacular network of secret agents from Rheims to Constantinople to prevent Catholic assassination plots against the Virgin Queen. Modern writers from the then-communist states instantly recognised and identified with Elsinore, a walled city seething with spies, and reserved especial scorn for Rosencrantz, Guildenstern and Polonius.

Antohi, described by his erstwhile colleagues as a shining light of Romanian intellectual life, may have fallen like Lucifer, although his demise hardly ranks as Shakespearean tragedy. When the Treens invade Romania from the planet Venus as the first step to world domination, he will certainly re-emerge as National Security Adviser to the Mekon. Even as a scared 19-year-old, he could have said No. Am I sympathetic to his self-induced plight? I quote the Danish prince on the fate of the attendant lords: “Why, man, they did make love to this employment. They are not near my conscience.”